The ‘key trait’: having one gill cover or several gill covers

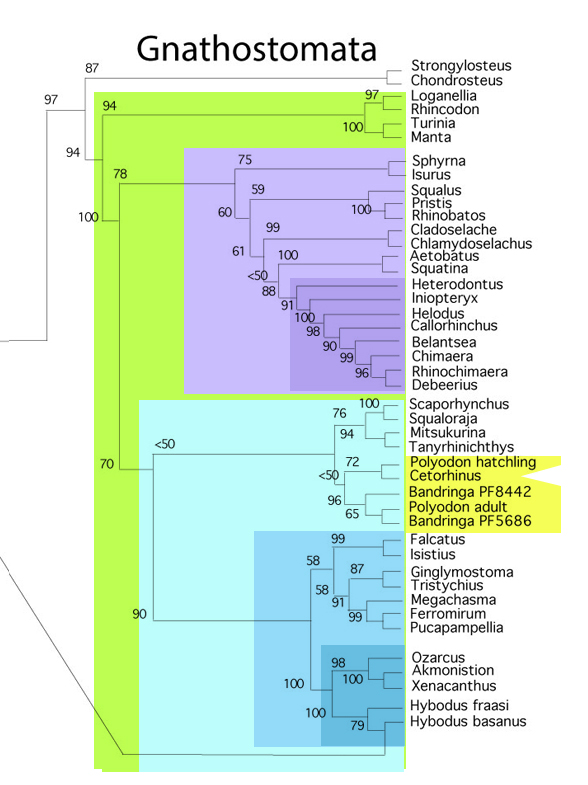

(as in sharks, Fig. 1) turns out to be a trivial trait in a matrix of 235 traits in the large reptile tree (= LRT, subset Fig. 2). Only one gene has to change to make one type of gill or the other as recently documented (see below).

What does ‘closely related’ actually mean?

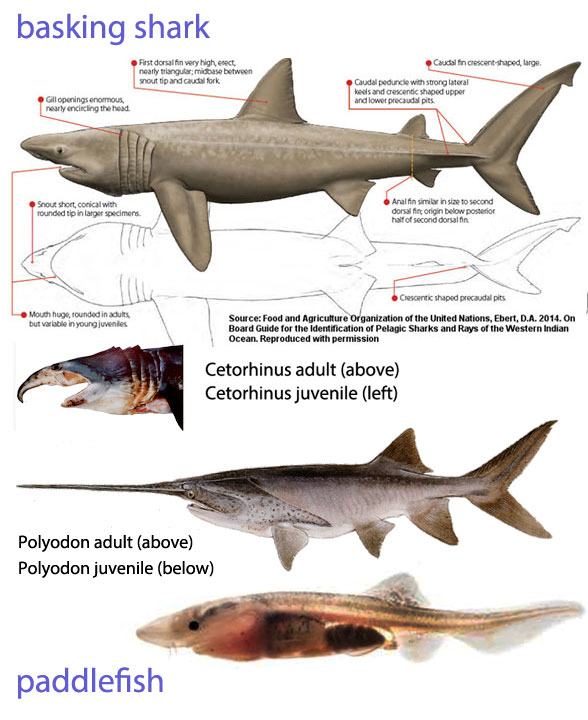

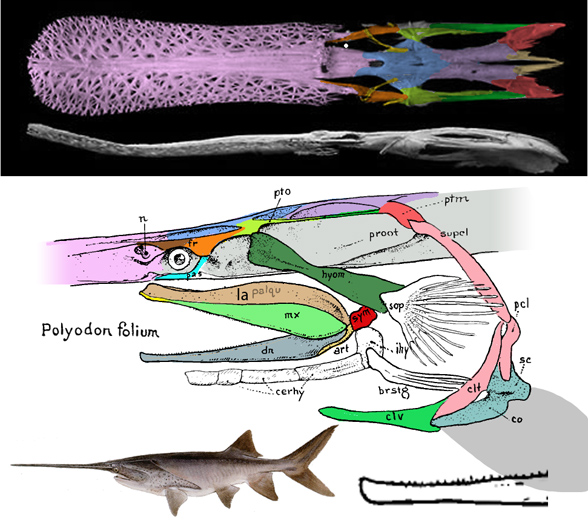

No other tested taxon shares as many traits with paddlefish (Polyodon) as the basking shark (Cetorhinus, Fig. 1) in the LRT. Someday a taxon might be added that nests between them. At present such taxa remain unknown and untested. Both taxa are derived from the Polyodon hatchling taxon (Fig. 3), which has a shorter rostrum and a more basking shark-like appearance overall. Back in the Silurian, pre-paddlefish hatchlings were likely much smaller and adults were likely the size of present day hatchlings, but that’s not a requirement. No other analysis that I am aware of has ever included paddlefish hatchlings as taxa, but that morphology is key to understanding various lineages within Chondrichthyes. So, here’s a case where adding a taxon is much more important than adding a character.

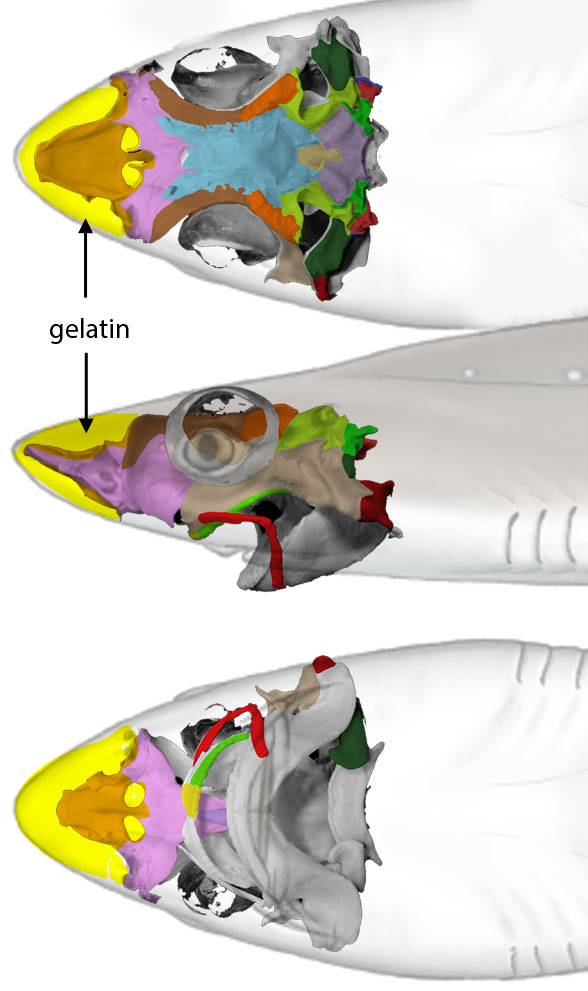

Note the gelatinous rostrum

in the paddlefish juvenile (Fig. 1). That trait is retained from mako sharks (Figs. 3, 6, as we learned earlier here. The rostrum of the adult basking shark is likewise filled with gelatin supported by a thin frame of cartilage (Fig. 4). The shark-like appearance of paddlefish has been noted previously. Previously the presence of one enormous gill cover in paddlefish has excluded them form prior shark studies. The LRT minimizes such taxon exclusion by simply adding taxa.

We’ve always known

that ratfish (with one gill cover, Fig. 3) nest with sharks (with several gill covers separating slits). No one has complained about that yet.

Then we learned

that sturgeons and Chondrosteus (with one gill cover, Fig. 3) nest basal to whale sharks and mantas (with several gill covers). The pattern of gill covers was presented and revised recently here.

Now

paddlefish (Polyodon) nests with basking sharks (Cetorhinus, Fig. 1) in the large reptile tree (LRT, 1785+ taxa, subset Fig. 2). Evolution is full of such trivial exceptions.

Paddlefish inhabit rivers. Basking sharks inhabit the sea.

They both feed the same way. Basking sharks reach 30 feet in length. Paddlefish reach 7 feet in length. The two likely went their separate ways in the Silurian (prior to 420mya), so they had plenty of time to evolve on their own since then.

A recent study on gill covers by Barske et al. 2020

“identify the first essential gene for gill cover formation in modern vertebrates, Pou3f3, and uncover the genomic element that brought Pou3f3 expression into the pharynx more than 430 Mya. Remarkably, small changes in this deeply conserved sequence account for the single large gill cover in living bony fish versus the five separate covers of sharks and their brethren.”

While comparisons to the feeding technique in paddlefish and basking sharks

appear in the literature (Matthews and Parker 1950, Haines and Sanderson 2017), these were presumed to be by convergence based on the single gill cover vs. multiple gill cover difference.

Relying on one, two or a dozen traits

to trump the other 234, 233 or 213 is called “Pulling a Larry Martin.” You don’t want to do that. Put aside your traditions, add taxa and let the unbiased software figure out where your taxon nests using the widely accepted hypothesis of maximum parsimony (= fewest changes) over a large set of character traits.

The present hypothesis of interrelationships

(Fig. 2) appears to be novel. If not, please advise so I can promote the earlier citation.

References

Barske L et al. (10 co-authors) 2020. Evolution of vertebrate gill covers via shifts in an ancient POU3f3 enhancer. PNAS 117(40):24876–24884.

Haines GE, Sanderson SL 2017. Integration of swimming kinematics and ram suspension feeding in a model American paddlefish, Polyodon spatula. The Journal of Experimental Biology, 10.1242/jeb.166835, 220, 23, (4535-4547), (2017).

Matthews LH, Parker HW 1950. Notes on the anatomy and biology of the basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus (Gunner)). Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 120(3):535–576.