Brazilian host, Alex Kellner,

begins his introductory lecture at 33:20 following instrumental music. The entire video extends to 1:30 hours.

Kellner acknowledges

“tremendous amount of dissent” among pterosaur researchers. 240 species. The large pterosaur tree (LPT, 269 taxa) tests 255 pterosaurs and 14 outgroup taxa. Kellner indicates widespread rejection of bipedalism in pterosaurs, but then shows Bennett’s 1997 reconstruction of an upright Nyctosaurus (Fig 1) based on UNSM 93000.

Kellner wonders about pterosaur origins

squamates (no one supports this, instead Kellner is referring to lepidosaurs like Huehuecuetzpalli (Fig 2) according to Peters 2007, still the only worker who has explored this possibility), basal archosaurs (lagerpetids? proterosuchids? euparkeriids? Bennett 1997), and archosaurs closer to dinosaurs (everyone else supports this, Padian 1987). Kellner cites three workers: David Hone, Mike Benton and Chris Bennett. Not sure how they match to the three theories. Actually, they don’t match at all.

Kellner suggests the reason for this lack of consensus

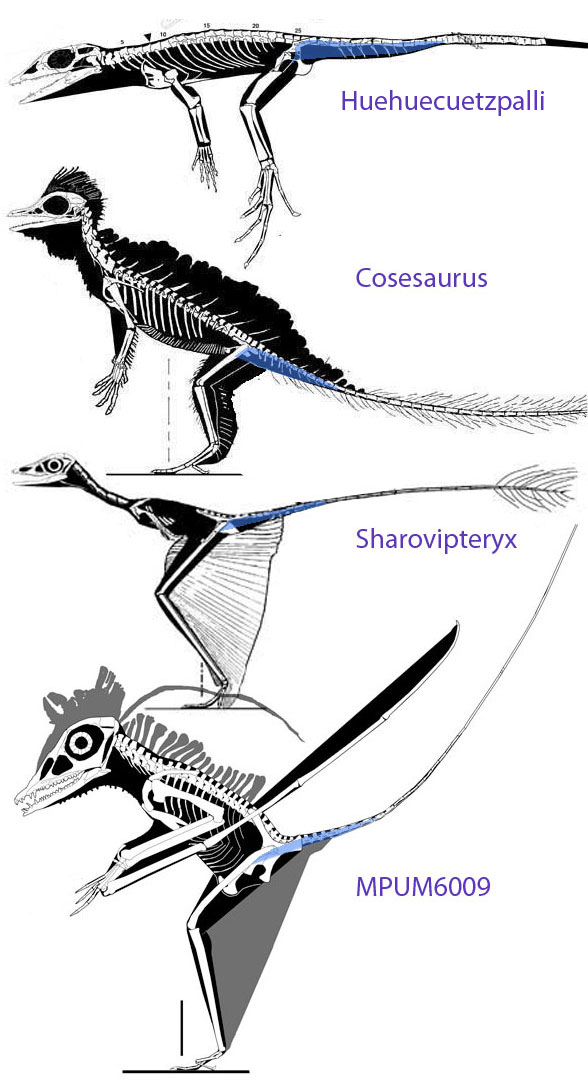

comes down to a lack of intermediate stages in the genesis of pterosaurs. That ignores Peters 2000, 2002, 2007 that provided half a dozen intermediates (Fig 2) going back to Macrocnemus and Huehueceutzpalli (Fig 2).

Remember Bennett’s curse?

“You will not be published and if you are published, you will not be cited.”

Kellner’s remarks represent just the latest version of this attitude.

Kellner’s pterosaur origin wish list:

1. “A piece of a pterosaur ?number [closed caption translation can’t deal with Kellner’s accent] because the whole skeleton would be, you know, too much to ask for”.

2. “I would love to find a creature that would if it could speak in English, Portuguese, whatever, would say I want to become a pterosaur when I evolve”.

That cuts straight to the issue. Professor Kellner would love to find this creature. He is not happy that an amateur discovered six such creatures in 2000 from previously published taxa. And since an amateur published on this (Kellner was a referee) he and other PhDs have not and will not examine this possibility, perferring instead to repeat textbook traditions and myths.

Kellner explains

all known pterosaurs already have “the same Bauplan as a pterosaur, with a a very large fourth wing finger. a large metacarpal, a deltopectoral crest of the humerus and also the sternum.”

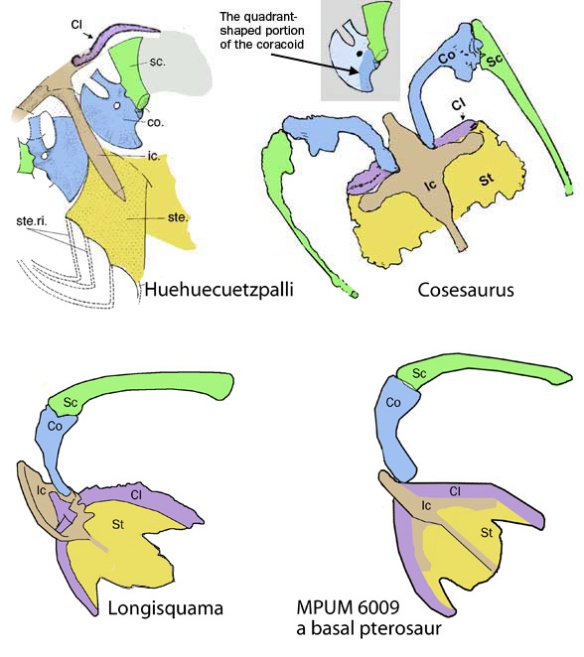

This is a wish list. A myth list. Kellner ignores actual evolutionary events in which the wings evolved last (Fig 2, Peters 2002), as in birds and bats. And, once again, this is why I am so disappointed with pterosaur workers and their workshops. Let’s remember that a pterosaur has a sternal complex = combined sternum, clavicles and interclavicles (Fig 3) that evolved from taxa like Huehuecuetzpalli (Fig. 2). Ask pterosaur professors why they keep their blinders on. We called this a curious lack of curiosity, especially for a scientist. It appears to come down to self-preservation and maintaining professional status, so this is human and forgivable, but at the same time, this is silly.

Kellner than semi-embraces the novel and invalid lagerpetid hypothesis

of pterosaur origins based on multi-cusped teeth (as in Longisquama, Fig 4)), brain case arguments and indeterminate lower jaw arguments. This is silly. He should be adding taxa to determine a last common ancestor in phylogenetic analysis. He should not be cherry-picking traits. This always leads to trouble.

It is notable that taxa cited in Peters 2000 are once again omitted, just as they were omitted from Hone and Benton 2009. This is not good science, but it has been acceptable science in academic circles for over two decades.

Kellner puts the lagerpetid origin hypothesis blame on cladistics,

“That’s the result and that’s what we have to accept,” he says. Curious that lagerpetid supporters are all from South America where lagerpetids are found. Despite his own doubts Kellner concludes the lagerpetid hypothesis is a breakthrough. This is bad science. Then Kellner acknowledges and dismisses Scleromochlus from Scotland (Fig 5), which he reports, “there’s not even a bone there, but there were impressions.”

Kellner otherwise ignores the issue of two decades of taxon exclusion (Fig 2).

Question for Kellner:

Why even bring up the subject of pterosaur origins if you have nothing valid to base your talk on? This is called a waste of time delving into one fantasy = invalid hypothesis after another.

Question from Kellner:

“How do you turn a lagerpetid into a viable pterosaur?”

Answer: you don’t. Seek your pterosaur ancestors elsewhere (Fig 2).

Answer from Kellner:

“I want to see something in the hand, (Fig 5) I want to see something in their arms, the pelvis, they have a pubischtic plate.”

See figure 6.

If Kellner is looking instead for the pterosaurian prepubis

Kellner can find that in Cosesaurus, Sharovipteryx and Longisquama (see Fig 6). But he and others don’t want to go down that path.

At 50:35 Kellner blames the current phylogenetic arguments

on incomplete material. This is so short-sighted. We have so many wonderfully complete specimens that never enter phylogenetic analyses, other than the LPT.

Once again, taxon exclusion, not incomplete material, is the number one issue facing paleontology in general, and specifically in pterosaurs. Workers need to build their own wide gamut phylogenetic analysis to find out for themselves how pterosaurs are interrelated. 200+ taxa is the number to shoot for.

I am so glad

that I did not have to suffer under the tutelage of current professors in order to study pterosaurs and their precursors. I was lucky that Sharovipteryx and Longisquama (Figs 2–4) came to my hometown at the moment I was curious enough and ready to study them. I was lucky that Paul Ellenberger provided me with unpublished material on his little Cosesaurus. His observations enhanced my freshman studies of this important fossil wrapped in toilet paper in Barcelona. I was lucky that, like Kellner, everyone else studying pterosaurs was looking for something in the wing-finger and hand, not realizing that wings came last in pterosaur evolution (Peters 2002), as they did in birds and bats. I studied the feet first (Peters 2000a) and the rest followed. I was lucky that David Hone rejected my update on Cosesaurus and kin. That frustration with academic corruption and their lack of curiosity lead to the creation of ReptileEvolution.com and PterosaurHeresies.Wordpress.com.

Over the last 12 years that drive to learn led to the addition of 2292 taxa in the LRT plus 269 taxa in the LPT without the intervention of professional gatekeepers who continue to omit pertinent taxa in their hope to discover the origin of pterosaurs themselves. Some things cannot be discovered twice.

You can recover the origin of pterosaurs yourself by repeating this online experiment. Add taxa. That’s all takes. Let us all know if your results with a similar wide gamut taxon list confirm, refute or modify published analyses, including the traditionally ignored LPT.

References

Bennett SC 1996. The phylogenetic position of the Pterosauria within the Archosauromorpha. Zoolological Journal of the Linnean Society 118: 261–308.

Bennett SC 2008. Morphological evolution of the forelimb of pterosaurs: myology and function. Pp. 127–141 in E Buffetaut and DWE Hone (eds.), Flugsaurier: pterosaur papers in honour of Peter Wellnhofer. Zitteliana, B28.

Carroll and Thompson 1982. A bipedal lizardlike reptile fro the Karroo. Journal of Palaeontology 56:1-10.

Dalla Vecchia FM 2009. Anatomy and systematics of the pterosaur Carniadactylus (gen. n.) rosenfeldi (Dalla Vecchia, 1995). Rivista Italiana de Paleontologia e Stratigrafia 115 (2): 159-188.

Ellenberger P and de Villalta JF 1974. Sur la presence d’un ancêtre probable des oiseaux dans le Muschelkalk supérieure de Catalogne (Espagne). Note preliminaire. Acta Geologica Hispanica 9, 162-168.

Hone DWE and Benton MJ 2007. An evaluation of the phylogenetic relationships of the pterosaurs to the archosauromorph reptiles. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 5:465-469. PDF online

Hone DWE and Benton MJ 2008. Contrasting supertree and total-evidence methods: the origin of the pterosaurs. In: Hone DWE, Buffetaut E, editors. Flugsaurier: pterosaur papers in honour of Peter Wellnhofer. Vol. 28. Munich: Zittel B. p. 35-60.

Nesbitt SJ 2011. The early evolution of archosaurs: relationships and the origin of major clades. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 352: 292 pp.

Nopcsa F 1931. Macrocnemus nicht Macrochemus. Centralblatt fur Mineralogie. Geologic und Palaeontologie; Stuttgart. 1931 Abt B 655–656.

Peabody FE 1948. Reptile and amphibian trackways from the Lower Triassic Moenkopi formation of Arizona and Utah. University of California Publications, Bulletin of the Department of Geological Sciences 27: 295-468.

Peters D 2000a. Description and Interpretation of Interphalangeal Lines in Tetrapods. Ichnos 7:11-41.

Peters D 2000b. A reexamination of four prolacertiforms with implications for pterosaur phylogenesis. Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia 106: 293–336.

Peters D 2002. A New Model for the Evolution of the Pterosaur Wing – with a twist. – Historical Biology 15: 277–301.

Peters D 2007. The origin and radiation of the Pterosauria. In D. Hone ed. Flugsaurier. The Wellnhofer pterosaur meeting, 2007, Munich, Germany. p. 27.

Peters D 2009. A reinterpretation of pteroid articulation in pterosaurs. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29: 1327-1330

Renesto S and Avanzini M 2002. Skin remains in a juvenile Macrocnemus bassanii Nopsca (Reptilia, Prolacertiformes) from the Middle Triassic of Northern Italy. Jahrbuch Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlung 224(1):31-48.

Sharov AG 1971. New flying reptiles from the Mesozoic of Kazakhstan and Kirghizia. – Transactions of the Paleontological Institute, Akademia Nauk, USSR, Moscow, 130: 104–113.

Snyder RC 1954. The anatomy and function of the pelvic girdle and hind limb in lizard locomotion. American Journal of Anatomy 95:1-46

Wild R 1978. Die Flugsaurier (Reptilia, Pterosauria) aus der Oberen Trias von Cene bei Bergamo, Italien. Bolletino della Societa Paleontologica Italiana 17(2): 176–256.

Wild R 1993. A juvenile specimen of Eudimorphodon ranzii Zambelli (Reptilia, Pterosauria) from the upper Triassic (Norian) of Bergamo. Rivisita Museo Civico di Scienze Naturali “E. Caffi” Bergamo 16: 95-120.

pterosaurheresies.wordpress.com/2011/07/16/what-exactly-is-a-pterosaur-part-3-of-3/

reptileevolution.com/pterosaur-wings.htm

Peters D unpublished update on Cosesaurus, Sharovipteryx and Longisquama.

People seem to rail on you for your pterosaur ancestors and phylogeny, saying that your character dataset is too small, when these people exist https://pterosaurnet.blogspot.com/

I hope you can still review sites, I discovered this site about a year ago and I’m waiting for somebody to call it out. Apparently, Epidexipterx is a sister to Tupandactylus and Scansoriopteryx is a basal stem-pterosaur. Psittacosaurus is also a compsognathid.

Yeah, I looked at Pterosaurnet years ago. I have not paid attention since then.

Yes, people rail on the LRT for a too small character set. This started when the current taxon list was 240 (now 2297 taxa). They are following textbooks. I am adding taxa (including fish!) and the character list still works. It won’t work in splitting extant crocodiles from each other. It will work splitting gavials from crocs and gators. I rail on other workers for too few taxa in nearly every post presented here. Ideally you should be able to test as many taxa as possible with as few multi-state characters as possible. Remember, we’re trying to lump and separate taxa, not characters.