Back in the early days of paleontology

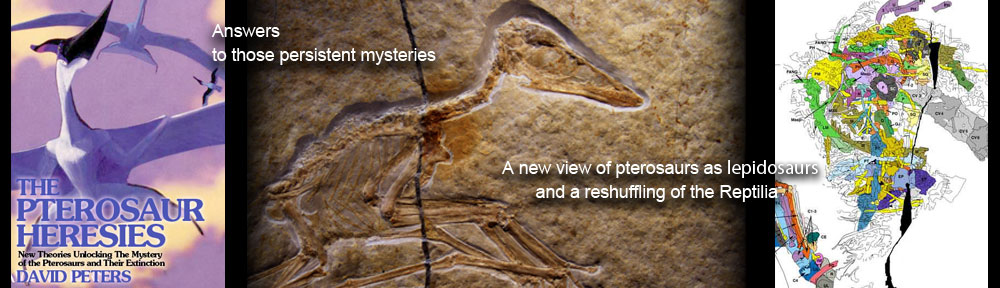

Fritsch (= Frič) 1880, 1881 described this Late Cretaceous (Turonian, 92 mya) small pterosaur partial wing series (Figs 1, 2) as a ‘Cretaceous bird’. Hence the name, Cretornis. Fritsch thought the humerus was a bird coracoid.

More recently

Cretornis was redescribed by Averinov and Ekrt 2015 who reported that Lydekker 1888 was “the first to recognize the pterosaur nature of the specimen.”

Averinov and Ekrt 2015 reported,

“Cretornis hlavaci Fric, 1881 from the Upper Cretaceous (Turonian) of Czech Republic is a valid taxon referred to Azhdarchoidea based on having a saddle-shaped humeral head, pneumatic foramen on proximal humerus present on anterior side and absent on posterior side, elongate deltopectoral crest with subparallel proximal and distal margins, pneumatic foramen absent on distal side of humerus, metacarpals IeIII not articulated with carpus and displaced on anterodorsal side of wing metacarpal, and wing metacarpal much longer than humerus.”

Azhdarchoidea is an invalid clade comprised of unrelated taxa (azhdarchids and tapejarids) whenever more taxa are added to analysis.

“Jianu et al. (1997: non-paginated abstract) have studied the holotype of C. hlavaci and found that it is “clearly pteranodontid based on having a caudally directed ulnar crest, a warped deltopectoral crest, and a triangular cross-section of the distal end. All these claims are incorrect.”

By contrast, Fernandes et al 2022

nested Cretornis basal to Muzquizopteryx, Alcione and several Nyctosaurus specimens, two nodes apart from several Pteranodon specimens.

Nyctosaurs all have a hatchet-shaped deltopectoral crest not seen in Cretornis.

Fernandes et al 2022 report,

“Phylogenetic analysis was conducted using TNT version 1.5 using the matrix by Longrich et al. 2018, which added new characters to the Andres et al. 2014 matrix and also includes additional taxa from the Late Cretaceous.”

Andres et al 2014 suffered from taxon exclusion and too much ambition + imagination as the team thought they had scraps from ‘the earliest pterodacytyloid’, but actually had scraps from a coeval gracile dorygnathid, Sericipterus, from the same formation. Brian Andres is a co-author on Fernandes et al 2022. So they borrowed a flawed cladogram.

Ferrnandes et al. still nest azhdarchids with taperjarids due to taxon exclusion. They also nest toothy ornithocheirids with ‘toothless’ pteranodontids. Those are traditional mistakes widely accepted by pterosaur workers for the last twenty years due to excluding tiny Jurassic pterosaurs.

Too little is known of Cretornis

to attempt to nest it in the large pterosaur tree (LPT, 262 taxa). However a scaled comparison of two pterosaur humeri is educational (Fig. 1). Pterosaur workers would benefit by doing this with scrappy taxa to facilitate and demonstrate (rather than just describe) comparisons. Pterosaur workers could have benefited from using DGS since 2003, but remain unlikely to do so, even though other paleo workers have adopted the method and practice of coloring bones.

Juvenile, primitive or small?

Averninov and Ekrt report on the Cretornis humerus, “The distal epiphysis is fully ossified and fused with the shaft.”

Or is it? The elbow appears to be incomplete and poorly ossified compared to the larger specimen from Kansas (Fig 1). Moreover, the Cretornis phalangeal shafts were preserved better than the phalangeal joints (Fig 2), suggesting immature (= softer) ossification at the joints.

Given this evidence, let’s consider the possibility that Cretornis is a juvenile Pteranodon ingens, traditionally known from the Santonian of Kansas, only 5 million years later.

Another possibility: the basalmost Pteranodon, (or the largest Germanodactylus) YPM 1179 (Fig 3), is known from a skull that would have been just about the right size to match the Cretornis wing (Fig 2).

It’s not surprising

to find small Early Cretaceous Pteranodon specimens in northern Europe. After all that’s where their ancestors, the Late Jurassic germanodactylids (Fig 3), are to be found (Peters 2007). Unfortunately this hypothesis, based on including traditionally excluded taxa, has been suppressed by academics like Andres in favor of linking toothless pteranodontids with toothy ornithocheirds. Here is the large pterosaur tree (LPT, 262 taxa), so you can see for yourself how all large pterosaurs are size convergent. All major pterosaur clades arise during phylogenetic miniaturization with taxa down to the size of sparrows and hummingbirds.

If you know any pterosaur specialists

remind them its time to start catching up to common knowledge. Tell them its time to add taxa, especially tiny taxa, to better understand pterosaur interrelationships. Unfortunately, this is the one thing they refuse to do. Not sure if this is due to fear, anger or laziness. Ask them.

Seems odd for a scientist to avoid testing additional taxa,

just because an amateur made the suggestion 15 years ago, but that’s their historic pattern.

On a similar note,

here again is the timeline of pterosaur origin studies documenting how pterosaur scientists have avoided certain taxa, hypotheses and citations. It’s almost as if… if it’s not in Benton’s textbook, it’s not going to be considered. That means paleontology at the university level will continue slowing to a stall, ignoring new discoveries in favor of what can be taught out of aging textbooks, unless it comes out of English universities.

References

Andres B, Clark J and Xu X 2014. The earliest pterodactyloid and the origin of the group. Current Biology 24, 1011–1016.

Averianov, A and Ekrt B 2015. Cretornis hlavaci Frič, 1881 from the Upper Cretaceous of Czech Republic (Pterosauria, Azhdarchoidea)”. Cretaceous Research. 55: 164–175.

Fernandes AE et al. 2022. Pterosaurs from the Late Cretaceous of Angiola. Diversity 2022, 14, 741. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14090741

Fritsch, A., 1880, Ueber die Entdeckung von Vogelresten in der böhmischen Kreideformation (Cretornis Hlaváči), Sitzungsberichte der königlichen-böhmischen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften in Prag 1880: 275–276.

Peters D 2007. The origin and radiation of the Pterosauria. Flugsaurier. The Wellnhofer Pterosaur Meeting, Munich 27