A somewhat recent paper by Botelho et al. 2015

looked at the embryological changes that axially rotate metatarsal 1 to produce a backward-pointing, opposable, perching pedal digit 1 (= hallux).

Hallux rotation phylogenetically

Botelho reports: “Mesozoic birds closer than Archaeopteryx to modern birds include early short-tailed forms such as the Confuciusornithidae and the toothed Enantiornithes. They present a Mt1 in which the proximal portion is visibly non-twisted, while the distal end is offset (“bent”) producing a unique “j-shaped” morphology. This morphology is arguably an evolutionary intermediate between the straight Mt1 of dinosaurs and the twisted Mt1 of modern birds, and conceivably allowed greater retroversion of Mt1 than Archaeopteryx.”

“D1 in the avian embryo is initially not retroverted9, and therefore becomes opposable during ontogeny, but no embryological descriptions address the shape of Mt1, and no information is available on the mechanisms of retroversion.”

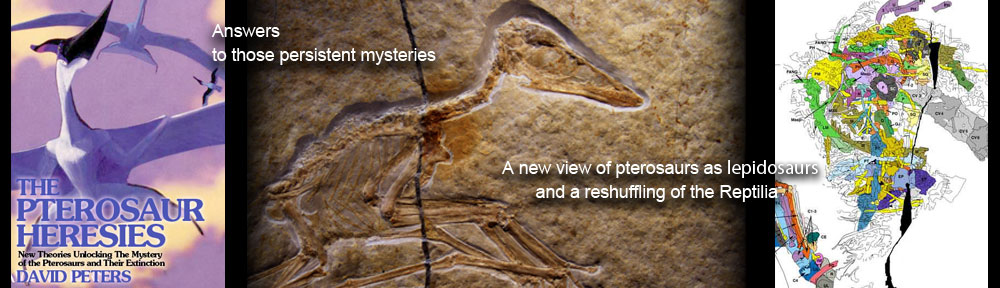

Figure 1. Pes of the most primitive Solnhofen bird, the Thermopolis specimen. This digit 1 never left the substrate.

In Tyrannosaurus,

(Fig. 2) the entire metatarsal 1 with pedal digit 1 is rotated just aft of medial by convergence. It’s not axially rotated. It’s just attached to the palmar side of the pes. This pedal digit 1 was elevated above the substrate.

Figure 2. The semi-retroverted pedal digit 1 of Tyrannosaurus rex in two views. This digit 1 was elevated above the substrate.

In some birds

like the woodpecker, Melanerpes, and the unrelated roadrunner, Geococcyx, pedal digit 4 is also retroverted. Sorry, I digress.

Further digression

The axial rotation of pedal digit 1 in birds is convergent with the axial rotation of metacarpal 4 in Longisquama (Fig. 3) and pterosaurs. In both taxa the manus was elevated off the substrate and permitted to develop in new ways. Manual digit 4 never leaves an impression in pterosaur manus tracks… because it is folded, like a bird wing, against metacarpal 4. In Longisquama such extreme flexion is not yet possible.

Figure 3. Longisquama left and right manus traced using DGS then reconstructed (below). This is a very large hand for a fenestrasaur and manual digit 4 is oversized and the metacarpal is axially rotated, as in pterosaurs. Manual digit 5 is useless, but not yet a vestige. A pteroid is present, as in Cosesaurus. The coracoid is elongate as in birds. The sternum, interclavicle and clavicle are assembled into a single bone, the sternal complex, as in pterosaurs.

Note the lack of space between

the radius and ulna in Longisquama. This is what also happens in pterosaurs. It prevents the wrist from pronating or supinating, as in birds and bats… which means, the forelimb is flapping, not pressing against the substrate, nor grasping prey. That means all those images of Longsiquama on all fours are bogus. Now you know.

So now we come full circle

While the toes of birds axially rotate and the wing metacarpal of pterosaurs axially rotates, the forearms of birds, pterosaurs and Longisquama do not axially rotate. No one wants their wing to twist.

References

Botelho JF, Smith-Paredes D, Soto-Acuña S, Mpodozis J, Palma V and Vargas AO 2015. Skeletal plasticity in response to embryonic muscular activity underlies the development and evolution of the perching digit of birds. Article in http://www.Nature.com/Scientific Reports · May 2015 DOI: 10.1038/srep09840

That Tyrannosaurus pes is articulated incorrectly. Norell and Makovicky (1997) showed the distomedial scar was not the articulation point for metatarsal I in theropods. It’s actually for the gastrocnemius muscle. See Middleton (2003) as well.

That makes perfect sense based on phylogenetic bracketing.

Actually, the foot on that specimen is mounted correctly. The spot where MT 1 attaches is not a muscle attachment scar.

I know that’s where you placed it in your 2003 monograph, but are there articulated tyrannosaur (or other theropod) specimens that have that positioning?

yes.

:|

Go to the RTMP sometime. They’ve got a couple of articulated tyrannosaur feet on display.