Everyone knows about the various flightless birds: the penguin, the dodo, the ostrich… the list goes on. There are no flightless bats. And no one has ever discovered a flightless pterosaur… until now. Flightless pterosaurs have been the subject of speculation and science fiction. Henderson (2010) considered Quetzalcoatlus and its giant kin to be too large to fly. Not many workers agree with him. You’ll see why later.

Now we know what a flightless pterosaur really looks like. And it wasn’t all that big.

SoS 2428 (Figure 1) is a roadkill fossil that only Wellnhofer (1970) published on in the modern era. He described it as a “variation” of Pterodactlylus longicollum and gave it the number 57 in his catalog of “pterodactyloid” pterosaurs from Late Jurassic

Solnhofen strata. Others who viewed the fossil agreed. It was considered nothing special and the distal wings were considered missing. SoS 2428 has never been included in prior cladistic analyses. It wasn’t worth the effort. That became the traditional view. Then I tested it.

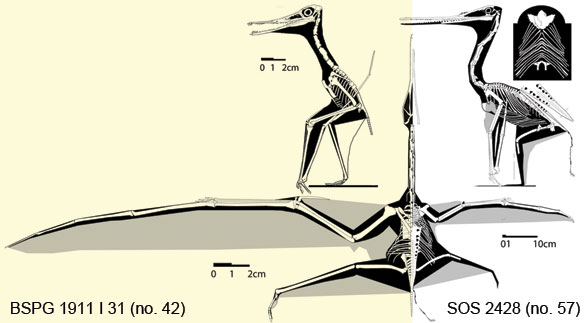

Figure 1. Click to enlarge. The first flightless pterosaur in situ. SOS 2428 is preserved crushed but articulated. The mandible appears on the plate, but the skull is visible beneath the plate. Other parts represent counterplates.

While similar to Pterodactylus longicollum in overall proportions, SoS 2428 had a flat rostrum, ultra-wide gastralia, ultra-long ribs, a hyper-elongated pelvis and distinct manual phalanx proportions (the feet are missing unfortunately). In cladistic analysis, SoS 2428 nested far from the holotype of Pterodactylus and its sister, P. longicollum. A reduced pectoral girdle and vestigial distal wing phalanges indicate this pterosaur could not fly. Further hampering its volant abilities, SoS 2428 had a huge belly supported by enormously elongated hips and a sacral region that expanded to over 60 percent of the torso, crowding up the dorsal ribs.

Note the similarities in position, shape and size between m4.3 and rib #9. Also note the similarities between the coracoid and rib #10, and the scapula and rib #11. Did you see the joint between m4.1 and m4.2? Find it difficult to locate the humerus, radius and ulna? Join the crowd. I had trouble too, but I kept at it knowing there were unidentified elements in the fossil. This paper was rejected because several reviewers reported they looked at the fossil without seeing what I describe here.

All these differences had gone unnoticed because no one had ever attempted to produce an accurate tracing of this difficult specimen. Wellnhofer (1970) only traced the easy to see elements: some teeth and a femur among them. Interpretation is difficult, but the DGS (digital graphic segregation) method using Adobe Photoshop came through, segregating the ribs from the gastralia from the rib-like wing and shrunken pectoral elements (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Click to enlarge. The torso of the flightless pterosaur, SOS 2428, along with three digital tracings segregating the ribs, gastralia, spine, pectoral and wing elements.

SoS 2428 clearly represents a new and so far unnamed genus and species. Closest sister taxa include Huanhepterus, BSPG 1911 I 31, Wellnhofer’s No. 42 and SoS 2179 all of which have been considered close to ctenochasmatids or pterodactylids, but actually represent a clade close to azhdarchids, like Quetzalcoatlus.

No. 42 is the best known of this clade and it had proportions that caused Wellnhofer (1970) to nest it with Pterodactylus. Clearly it was able to fly. SoS 2428 had a longer rostrum, a longer neck, a longer sacrum, longer dorsal ribs, longer gastralia, a smaller pectoral girdle and wings (especially the distal elements) and a longer femur. With such small wings and such a large belly, SoS 2428 could not fly, but it could still flap.

Quetzalcoatlus had a vestigial distal wing phalanx, but it retained a large pectoral girdle, long wings and a small torso, thus it did not follow the pattern of SoS 2428, the flightless pterosaur. Quetzalcoatlus retained the traits of a volant pterosaur.

Fig. 3. Lateral, ventral and dorsal views of SoS 2428 alongside No. 42, a volant sister taxon. Note the reduced wings and pectoral girdle of no. 57, which also had an expanded gastralia basket and elongated dorsal ribs and a hyperelongated pelvis. With such small wings and such a large belly, it could not fly, but it could still flap.

Animals with a larger belly are often plant eaters that require a larger gut to digest their diet. SoS 2428 retained a large sternum, which means the pectoral muscles remained large for adducting the humeri perhaps for quadrupedal locomotion, but certainly for flapping. The elongated femur extended slightly anterior to the pelvis, but still was unable to place the hypothetical feet beneath the shoulder glenoid, the center of balance, as in all other pterosaurs, without lifting the hands off the substrate. Thus a quadrupedal pose was likely during beachcombing and feeding, while a bipedal pose supported by the anterior extension of the sacrum and ilium, was employed at other times.

A larger pterosaur with a longer rostrum, SoS 2179 was derived from SoS 2428. Only the skull is known. See it here. We can only imagine that the wings were smaller and the belly was bigger.

References:

Henderson DM 2010. Pterosaur body mass estimates from three-dimensional mathematical slicing. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30(3):768-785.

Wellnhofer P 1970. Die Pterodactyloidea (Pterosauria) der Oberjura-Plattenkalke Süddeutschlands. Abhandlungen der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, N.F., Munich 141: 1-133.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328388664_First_Flightless_Pterosaur

Hello,

I would like to see more data on this amazing discovery. If you could email it to me, that would be great. A flightless pterosaur would be great to have in the annals of natural history, and if

I could see what you saw, that would be great.

Thanks,

Mack

Not sure how else I can help you. What I saw is at

http://reptileevolution.com/sos2428.htm

and you can reassemble the images in Photoshop.