Böhme M et al 2019 reported,

“Many ideas have been proposed to explain the origin of bipedalism in hominins and suspension in great apes (hominids); however, fossil evidence has been lacking.”

Ironically, extant gibbons (Hylobates) and siamangs provide living evidence of bipedalism and suspension.

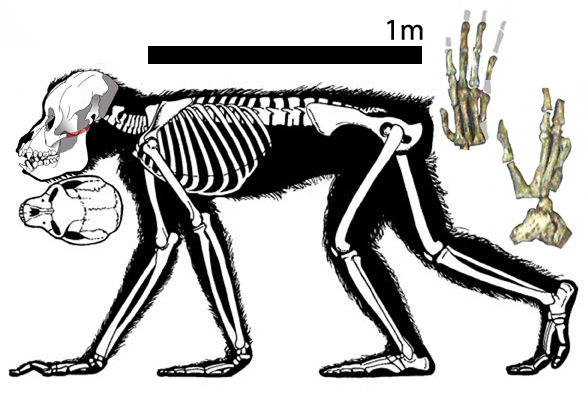

But to the authors’ point, gibbons are not considered ‘great apes’. Neither are the fossil transitional taxa between gibbons and humans (Fig 1) in the LRT.

When you cherry-pick taxa and clades like this, you might not discover what is sitting right beneath your nose.

Figure 2. The gibbon lineage leading to humans. At right is Australopithecus, a bipedal ape by convergence with humans.

Böhme M et al continued,

“It has been suggested (in Begun 2004) that bipedalism in hominins evolved from an ancestor that was a palmigrade quadruped (which would have moved similarly to living monkeys), or from a more suspensory quadruped (most similar to extant chimpanzees).”

Gibbons are not palmigrade. They are bipedal like humans (Fig 1). The last common ancestors of apes and humans, a pre-giibbon like Proconsul (Fig 2), was likely palmigrade, as are all monkeys.

Figure 3. Proconsul displays primitive traits for chimps and humans. It did not walk on its knuckles.

Böhme M et al continued,

“Here we describe the fossil ape Danuvius guggenmosi (from the Allgäu region of Bavaria) for which complete limb bones are preserved, which provides evidence of a newly identified form of positional behaviour—extended limb clambering.”

Sounds like a gibbon (Fig 1).

“The 11.62-million-year-old Danuvius is a great ape that is dentally most similar to Dryopithecus and other European late Miocene apes.

According to Wikipedia, Pilbeam and Simons 1971 “separated the genus–which included specimens from across the Old World at the time–into three subgenera: Dryopithecus in Europe, Sivapithecus in Asia, and Proconsul in Africa. Afterwards, there was discussion over whether each of these subgenera should be elevated to genus.

“With a broad thorax, long lumbar spine and extended hips and knees, as in bipeds, and elongated and fully extended forelimbs, as in all apes (hominoids), Danuvius combines the adaptations of bipeds and suspensory apes, and provides a model for the common ancestor of great apes and humans.”

Sounds like a gibbon (Fig 1).

There was dissent in the academic community

Begun et al 2020 wrote, “Williams and colleagues question our interpretation of the evolutionary importance of extended limb clambering for the emergence of great ape suspension and hominin bipedalism2 by casting doubt on the morphological evidence for bipedalism in Danuvius. Specifically, they question the hip mechanics, the reported orthogonal set to the distal tibia and the evidence for a functionally elongated lumbar spine by re-interpreting the position of the diaphragmatic vertebra.”

“Williams et al. 2020 discovered a typographical error regarding hip mechanics in the supplementary information of our original paper: iliopsoas is obviously a hip flexor, as Williams et al. state (as well as being an external rotator). However, our inference of the probable orientation of the ilium in Danuvius is based on the morphology of the proximal femur, which is consistent with habitual extension and enhanced gluteal abduction at the hip joint.”

“Extended limb clambering should not be confused with striding terrestrial bipedalism, which represents another form of positional behaviour. Danuvius has attributes that we interpret as functionally enabling arboreal bipedalism, but not striding terrestrial bipedalism.”

Take another look at gibbons. They do both types of bipedalism.

Here’s proof (Fig 1).

How rarely can you say ‘proof’ in paleontology]

References

Begun DR 2004. in Biped to Strider: The Emergence of Modern Human Walking (eds Meldrum DJ and Hilton CE) 9–33 (Kluwer).

Böhme, M, et al (8 co-authors) 2019. A new Miocene ape and locomotion in the ancestor of great apes and humans. Nature. 575 (7783): 489–493.

Böhme, M, et al (8 co-authors) 2020. Reply to: Reevaluating bipedalism in Danuvius. Nature 586 E4–E5.

Pilbeam D and Simons EL 1971. Biological sciences: humerus of Dryopithecus from Saint Gaudens, France. Nature. 229 (5, 284): 406–407.

Williams SA et al (4 co-authors) 2020. Reevaluting bipedalism in Danuvius. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2736-4.

wiki/Danuvius_guggenmosi

wiki/Dryopithecus

Surely DNA is the more useful tool here.

We know that Homo Sapiens are most closely related to Chimpanzees and Bonobos, not Gibbons. If what you are proposing was true, the genome reflect it. It does not.

Hi Sean. In deep time studies DNA = genomics recovers untenable results (eg matching chickens with ducks, cats with rhinos and bats, elephants with golden moles, etc). That tells us while DNA will help us locate criminals, errant fathers and long lost siblings, in deep time studies it cannot be trusted. Sorry.

For that reason we don’t know that we are closer to chimps. Traits say gibbons.

Your beef is with those who publish genomic results without wondering why results look so bizarre, defy logic and are not replicated in trait analyses.

Plus genomics tosses out fossils. Check your trusts and assumptions.