In parts 1, 2 and 3 of this series of rebuttals we examined the first portions of the new Tetrapod Zoology blog headlined, “Why the World has to Ignore ReptileEvolution.com. Here, in part 4, we’ll look at Darren Naish’s arguments against my interpretations of Longisquama and pterosaurs.

Longisquama

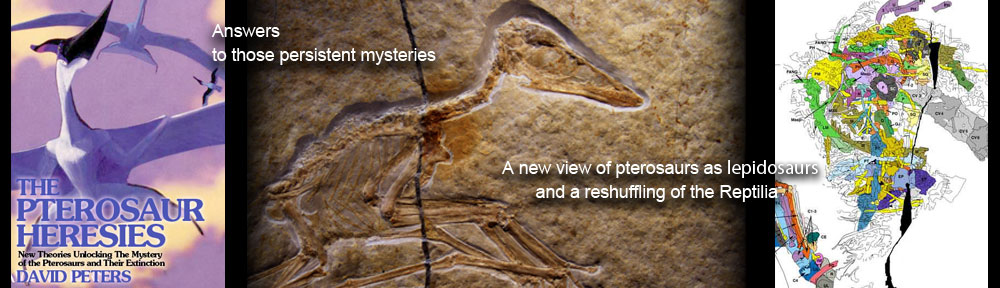

Perhaps the most elaborate reptile to ever walk this planet, Longisquama has perplexed paleontologists for decades, yet relatively few, other than Sharov (1970) and Peters (2000, 2002) have published skeletal tracings and reconstructions of this Triassic oddball. Darren republished my tracings of the Longisquama holotype, one for soft tissue and one for bones. These were originally traced at 600 dpi and quite large. Their reduction to web scale and screen is unfortunate, but unavoidable. Even so, the point was to map out where the elements could be found. They are difficult to see at any scale. Nothing is easy. All of the paired left and right elements were found twice, which should add to their credibility. The stomach area and hips are the most disarticulated. One hind limb is straightened out and has been traditionally mistaken for a displaced plume by all prior workers. So, its visible. The other limb is bent at about 170 degrees at the knee but oriented dorsally, so it was also camouflaged with the plumes. The feet were at the base of the plumes where Jones et al. (2000) reported subdivided feather shafts. These are actually unrecognized pedal phalanges. That’s why they appear subdivided. The tail parallels a plume and is likewise camouflaged by it.

There are no baby specimens in the slab. That was hopeful thinking in 2004 that did not make it into ReptileEvolution.com. So Darren mentions yet another item plucked from my garbage bin that is NOT in the website he is telling everyone to ignore.

Darren often mentions the term “weird” in connection with Longisquama, not noting that the weirdest aspect of the reptile has been widely observed, studied and written about, the plumes. I only added hind limbs, a pelvis, tail and some elongated fingers that anticipate the long wings of pterosaurs. The long legs are found in sister taxa, Sharovipteryx and the basal pterosaur MPUM6009. The pectoral complex and stem-like coracoids go back to Cosesaurus.

Darren claims that I said Longisquama-like plumes were present in ALL pterosaurs. Well, I didn’t say that in ReptileEvolution.com, so once again, Darren has mined my wastebasket for crap. Darren, for some reason you keep warning people away from stuff that doesn’t appear in ReptileEvolution.com…except in one place… the most basal pterosaur, the one most like Longisquama, the one and only MPUM6009. And, of course, this is what sister taxa do: share character traits. Cosesaurus had a frill. Huehuecuetzpalli had a dorsal frill (homologous to that found in Sphenodon). Not sure why I can’t find one on Sharovipteryx. Shows, I suppose, how quickly such frills can appear and disappear.

Darren presents another artist’s vision of Pteranodon with frills like Longisquama. He reports, “The Dave Peters vision of Pteranodon, as reconstructed by Nemo Ramjet (Mehmet Kosemen) in 2008. I’m no longer entirely sure whether Dave still supports the idea that pterosaurs looked like this, but he argues for all of the features you see here in his published articles (e.g., Peters 2004). Dave doesn’t like illustrations such as this as he thinks people are lampooning or making a fool of him. Maybe that’s so, but the fact remains that the reconstruction shown here (and those elsewhere in this article) is accurately based – without embellishment – on a reconstruction that Dave has produced himself.” If so, once again, no such illustration or reconstruction appears in ReptileEvolution.com, so Darren is showing you spooks that aren’t even present in the website. And he thinks this is justified. (I’m just glad he hasn’t talked to my mother about all the bad things I did growing up.)

Stage 4, Phylogenetic Nesting

Darren next tackles the large reptile tree. He reports, “As noted above, the general thinking on this issue is that pterosaurs are archosaurs, closely related to dinosaurs and their kin, and forming with them the clade Ornithodira. A list of anatomical characters appears to support this position.” Darren does NOT report that this list is extremely short and that a much longer list of anatomical characters can be found elsewhere, in the Fenestrasauria. Bennett (1996) commented that his list of pterosaur/archosaur traits included chiefly hind limb characters and that removal of those characters moved pterosaurs away from Scleromochlus and dinosaurs. This is a problem. In the real world, as demonstrated by any taxon, you can take away the skull or the limbs or anything in between and, for instance, pterosaurs (but it could be elephants), will not shift in the tree, but continue to nest with basal fenestrasaurs (or other elephants). That tells you pterosaurs are fenestrasaurs from head to toe. This also holds for all well-known reptiles. If they do shift they are most likely not nested correctly.

The Origin of Pterosaurs

Darren published a figure of mine showing a series of taxa from Cosesaurus to Austriadactylus and commented, “It looks good, but many of the details key to this hypothesis have been ‘discovered’ via Dave’s digital tracing technique and hence are not trustworthy or repeatable.” Then Darren, I suggest you discard those details, add some of your own and see what you get! That’s okay! Test to your own specs. Of course, I disagree with you on the possibility of repeatability of the details. That’s why I published all this data on ReptileEvolution.com so people could test and repeat my results. Once again, don’t dismiss the taxon list just because you dismiss the observer and his methods. Those fossils are still out there. Study them to your heart’s content. Do your own test. Tell us all what you find. Senter (2003) gave this a shot and, to my eye, bungled many character scores. See what you think.

The Return of the Thesis

Darren reports, “ReptileEvolution.com is a huge problem, and those of us involved in research on tetrapod evolution need to somehow counteract its influence.”

The Helveticosaurus Problem

Darren posted two of my Helveticosaurus figures, one with a new skull. Helveticosaurus is known from a complete skeleton, but no one, other than myself, has attempted to do a reconstruction using all the elements. The earlier illustration was based on a long shot photo (not very distinct). The new skull was added when a closeup of the skull appeared on the web. Darren remarks, “Dave frequently revises his reconstructions. That’s ok, but I’m often left confused why the differences between revisions are so great – is this because his digital tracing technique is utterly unreliable?” I would have to say, based on experience, that with higher resolution data, the technique becomes more reliable. Hence the improvements. However, in an effort to be all inclusive (as I can be) I grab data from every source I can. Sometimes that data is not so good. Other times: excellent. Trying is traditionally good in Science. Even failing is usually not frowned upon.

Competing Analyses

Darren writes, “The high visibility of ReptileEvolution.com is exacerbated by the fact that Dave’s ‘competitors’ – those who publish the sort of big-scale, taxon-heavy analyses that contradict his own trees – either have no internet presence at all, or are not interested in putting images, diagrams and other representations of specimens online.” There are large analyses in the literature, but nothing comparable to the scope of the large reptile tree with its 300 reptiles from all over and every age. Trees that apparently contradict mine, like the recent Gauthier et al. (2012) tree, (which IS online here) are typically missing many key taxa or are much smaller and more focused in scope. My tree is focused on basal taxa from every large clade. Darren also overlooks the presence of Wikipedia, which generally toes the traditional line. Thus the competitors are indeed online, but none have the scope of the large reptile tree. Not yet.

More in part 5.

References

Jones TD et al 2000. Nonavian Feathers in a Late Triassic Archosaur. Science 288 (5474): 2202–2205. doi:10.1126/science.288.5474.2202. PMID 10864867.

Peters D 2000a. Description and Interpretation of Interphalangeal Lines in Tetrapods. Ichnos 7:11-41.

Peters D 2000b. A reexamination of four prolacertiforms with implications for pterosaur phylogenesis. Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia 106: 293–336.

Peters D 2002. A New Model for the Evolution of the Pterosaur Wing – with a twist. Historical Biology 15: 277–301.

Peters D 2007. The origin and radiation of the Pterosauria. In D. Hone ed. Flugsaurier. The Wellnhofer pterosaur meeting, 2007, Munich, Germany. p. 27.

Peters D 2009. A reinterpretation of pteroid articulation in pterosaurs. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29: 1327-1330

Senter P 2003. Taxon Sampling Artifacts and the Phylogenetic Position of Aves. PhD dissertation. Northern Illinois University, 1-279

Sharov AG 1970. A peculiar reptile from the lower Triassic of Fergana. Paleontologiceskij Zurnal (1): 127–130.

Sharov AG 1971. New flying reptiles from the Mesozoic of Kazakhstan and Kirghizia. – Transactions of the Paleontological Institute, Akademia Nauk, USSR, Moscow, 130: 104–113.

Unwin DM and Bakhurina NN 1994. Sordes pilosus and the nature of the pterosaur flight apparatus. Nature 371: 62-64.

But, in your own tree, MPUM 6009 isn’t the sister taxon of Longisquama. Pterosauria as a whole is.

Why do you think so? Why shouldn’t different body parts be able to converge with those of different other animals? Why shouldn’t total evidence be necessary – the signal adds up, the noise cancels itself out –?

Imagine no pterosaurs after MPUM6009. They don’t exist or where never found. Plus I’m trying to point fingers at genera, not clouds of hopeful candidates.

re: not correctly nested: I know from experience. Having a wide gamut tree gives certain insight due to expanded opportunities for taxa to nest elsewhere that smaller, more focused trees do not have.

“And, of course, this is what sister taxa do: share character traits. Cosesaurus had a frill. Huehuecuetzpalli had a dorsal frill (homologous to that found in Sphenodon). Not sure why I can’t find one on Sharovipteryx. Shows, I suppose, how quickly such frills can appear and disappear.”

So you are grouping those taxa together based on the character trait of the frill, yet when Sharovipteryx doesn’t have one, it remains in the group because the character trait used as the paradigm for grouping the taxa is highly ephemeral. What?

I’m probably misinterpreting your comment (or putting too much weight on the importance of that character trait to classification), but this doesn’t quite seem to make sense. If the character trait is gained or lost so quickly, how can you use it to group taxa? That doesn’t seem to be a very reliable or secure way of establishing relationships to me. Then again, I am no expert.

This is only one trait. These taxa share a very large suite of traits among hundreds that I employ. I encourage you to see these taxa on ReptileEvolution.com where those shared and discrete traits are discussed. Also many of the earlier blogs here cover that topic. Use your keywords to find them.

Pingback: Over het ontstaan van kikkers, slangen, krokodillen | Tsjok's blog