If you ever wondered

how the under-slung parasagittal oral elements of jawless fish with a transverse hinge (Fig 1) evolved into the more familiar arc with paired lateral hinges (Figs 2–4), here’s a series of graphics that show a step-by-step evolution. This series applies only to the placoderm clade and all taxa that descended from placoderms.

As recovered earlier, stem tetrapod jaws developed in a different clade of fish. Thus the traditioinal clade, ‘Gnathostomata‘ is no longer monophyletic. See Birkenia for details.

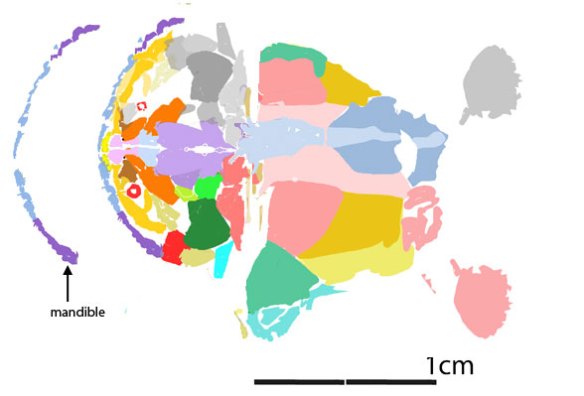

Rhinopteraspis

(Fig 1) demonstrates the jawless condition in pre-placoderms. The mobile oral elements opened like a castle draw bridge. Note the transverse hinge of the multiple elements and the parasagittal orientation of the medial elements, unlike the jaws in extant vertebrates.

The tentative genesis of jaws in Late Silurian Qilinyu

(Fig 2) demonstrates the transition from parasagittal elements in jawless pre-gnathostomes to lateral elements in basal gnathostomes. Note the disappearance of all but the anterior tips of the former mobile oral elements (Fig 1), now tentatively conjoined, but still moving in the same limited arc. This is a very weak jaw.

In phylogenetically miniaturized Bianchengichthys

(Fig 3) the jaw evolved into a greater arc that matched the rostral margin enabled by reduction of the nasal elements and migration of the once ventral nares. Whether the mandible elements were strongly conjoined or not cannot be determined from this tiny fractured fossil and its gracile mandible. Either way, the mandible was still fragile.

Not all primitive placoderm jaws were gracile and weak.

Coccosteus (Fig 4) also had an under-slung jaw, like Qilinyu (Fig 2), but it was sharp and robust. Note the similar ventral narial openings in Coccosteus and Qilinyu. Are these excurrent nares? And why do they not appear in the anterior view of Coccosteus where the ventral nasal plate lacks the perforations seen in ventral view? Here we also see the origin of palatal teeth (blue arc in ventral view) recapitulating in arc and chain of gracile elements the earlier origin of the mandible.

Evolution is a fascinating subject. I’m glad you’re along for the ride.

PS

Bothriolepis (FIg 5), another placoderm, did not move its mandibles. Instead it moved its nasals, rimmed by scraping premaxillae. The number of mandible elements in Bothriolepis corresponds with those of Rhinopteraspis (Fig 1), including those extra-wide medial elements with a narrow ‘neck’. Based on this example, the premaxilla also evolved several times. And of course it disappeared several times more. That is why phylogenetic analysis can be so vexing to score.

Variation builds upon variation.

References

Zhu et al 2016. A Silurian maxillate placoderm illuminates jaw evolution. Science 354.6310:334-336.

wiki/Gnathostomata

wiki/Qilinyu

wiki/Poraspis